This article is reposted from the Duke Kunshan University Language and Culture Center Official WeChat Account. Click to read the original article.

In this piece, Tong Yang (Haris) explores how female comedian Yang Li’s “ordinary but confident” joke created a new word of that meaning — “puxin” — that then ignited a controversy over gender roles in China. And then, how creative netizens turned the term into a pushback against the quest for excellence in Chinese society, and how it became a slogan for average people to be proud of their self-worth.

Simple banter from stand-up comedian Yang Li unexpectedly sparked heated Internet discussions starting in August 2020 which continue today. Yang’s joke was: “Why is he so confident, when he looks so ordinary?”

Then the joke exploded across China’s Internet into a viral new term. Creative netizens derived a new compound word “普信” or “pǔxìn” based on Yang’s performance. “Puxin,”“普信,” as a condensed version of “ordinary but confident” in which “普” means “ordinary” and “信” means “confident,” was initially used by Yang to satirize the phenomenon of mansplaining. But it was soon transformed by netizens to convey two broader meanings: One, a usage that more strongly criticized men for a tendency to traditionally assume superiority over women in China, and the other use of the term, something totally different: A celebration of “ordinary” people, in the face of dominant social values in China that continually demand excellence.

Such tradition-challenging meanings enable “普信” to be more than just a Chinese cultural keyword, reflecting “cultural values and ways of thinking and feeling,” (Pogosyan, 2017, p.1), but rather an intercultural product because it further mirrors the collision between the dominant culture and non-dominant cultures in China. “Puxin,” “普信,” “ordinary but confident” is so crucial for Chinese culture in the multicultural contemporary context because it reveals cultural collisions over gender and the constant striving for perfection in China.

These collisions are the ones between patriarchy and feminism, and between how others evaluate you in a social group (crucial to collectivism) and, on the other hand, self-recognition – crucial to individualism. With this insight, we can critically interpret usages of “puxin” in reality: when women use puxin to satirize men, they are essentially combating the patriarchal advantages men have. But when people begin to assert another meaning to the phrase – that being ordinary and confident is to be celebrated – they are rebelling against the intense and constant societal judgment in China to excel.

Puxin’s journey as a cultural keyword has been a winding one. In the original context, Yang Li used “ordinary but confident” to target mansplaining, as explicitly expressed in her segment about a male friend’s unsympathetic reaction to her break-up with a guy. In the joke, Yang Li imagines the internal monologue of her male friend who’s listening to her break-up tale in a sarcastic way. “This girl simply came to me to pour out [emotionally vent]? No way, she must want to learn something from me,” Yang said in her bit, aimed at the self-centered attitude of some males associated with “puxin.”

In the real world, women responded in kind with similar experiences. A hit comment under a video introducing the phenomenon of mansplaining on Bilibili (a popular Chinese video platform) found resonance with Chinese female netizens. One commenter, a female undergraduate majoring in sports science who goes by the username “Liu Xin can definitely get admitted,” described how she had experienced this regarding her knowledge of sports: “My male relatives ‘taught’ the rules of tennis to me – a trained tennis player.”

It wasn’t long before “puxin” (普信) went viral on Weibo, with #杨笠吐槽直男盲目自信# (#Li Yang venting about guys’ blind confidence#) reaching approximately 210 million hits and 84,000 discussions until now.

As the term raced across the Internet, “ordinary but confident” was afterward appropriated by female Internet users to a variety of scenarios in which men – intentionally or not – exhibited superiority over and overconfidence with women. Noteworthy was that some women began generalizing all men as lacking empathy, arrogant, and even manipulative. (P1-3; Images from Weibo)

Don’ t try to control me.

No men can reason with me except my dad.

Got nothing to say.

“So ordinary and so confident” (on the sticker)

Again, the confidence is deeply felt.

Yesyesyes, what you said is 100% right, never any problem with yourself, all others’ fault.

From a gender-focused perspective, “ordinary but confident” can reflect the collision between patriarchy and feminism when used to satirize certain habits and attitudes of men – habits and attitudes with a long history in Chinese thought. The patriarchal essence of ancient Chinese society can be exemplified by the Confucian “three cardinal guides” (a basic ethical standard in ancient China first articulated by Dong Zhongshu, a renowned educator, thinker, and statesman of the Han Dynasty in Chunqiu fanlu): “An official serves his ruler, a son serves his father, and a wife serves her husband.” The historical dominance of men over women was first dealt a heavy blow by the 1911 Revolution declaring the end of the Qing Dynasty and has been gradually chipped away at by attendant social progress. However, patriarchy has been so predominant for over 2000 years that fighting against its legacies remains a work-in-progress, a sign of which is the breeding ground of “普信,” “ordinary but confident.”

But if the fervor over “puxin” was women’s moment of pushback against the patriarchy, at least some men in China were just not having it.

While some men supported Yang Li and her right to satiric speech, others engaged in fierce rebuttals and accused her of starting a “gender war.”

A number of Chinese male netizens labeled by females as “普信男,” “ordinary but confident men,” were so offended by Yang Li’s comedy that they encouraged boycotts of products she endorsed. On January 12th, 2022, Yang Li was announced to be a guest on the talk show Shede Wise Figure, co-created by Shede Spirits Co Ltd, a highly-listed Chinese liquor company. Riding the wave of heated discussion about Yang Li, enraged male consumers boycotted Shede Spirits in protest of Yang’s appearance; the company’s shares on the secondary stock market dropped 1.94 percent on 17th January only, equating to a total market value of approximately 64.5 billion RMB or 8.94 billion USD lost (Laochen, 2022). Women’s use of the term “puxin” – and how it reflected their awareness of feminism and female empowerment – and the response to it from some men in China intensified the gender conflict online.

That is, until the use of the term changed again, and took on “a kinder, gentler” additional usage through netizens’ reimagining of it.

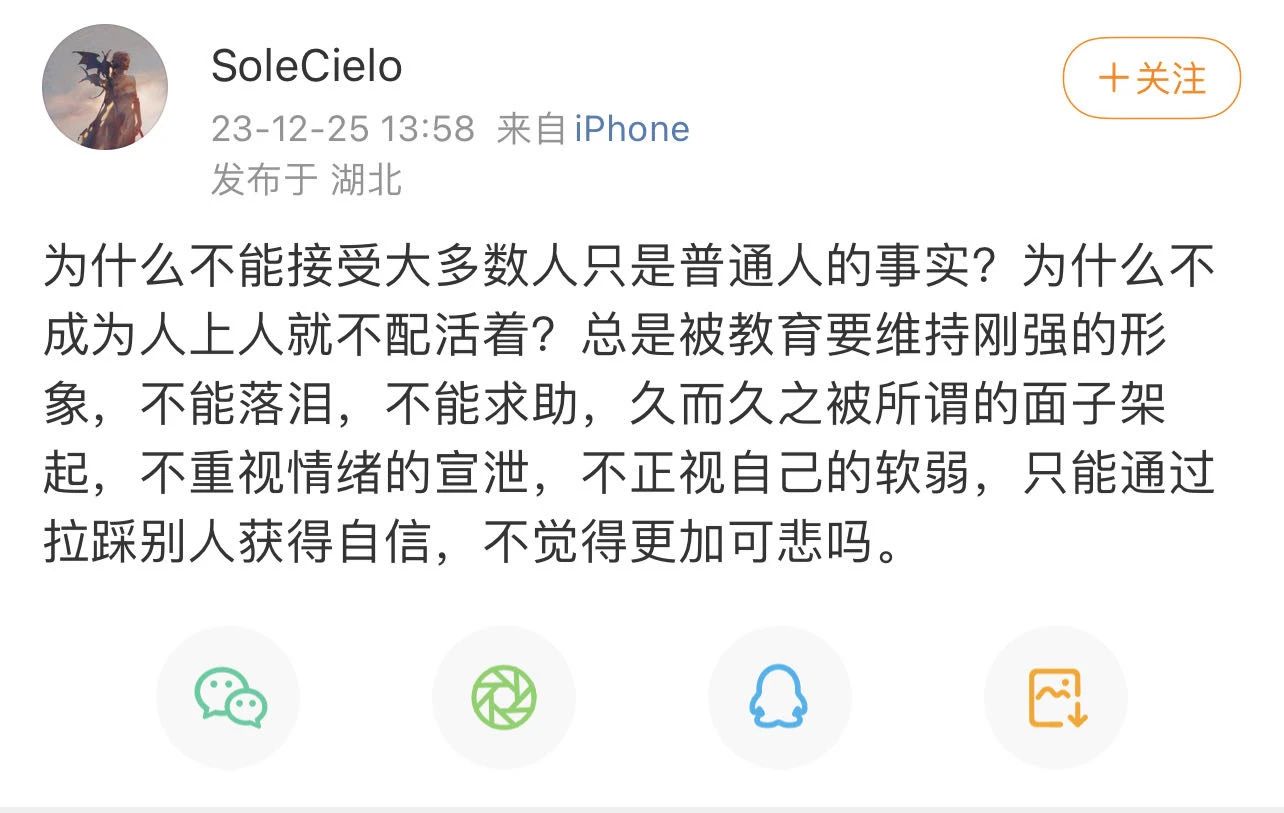

In April 2022, over the course of several days, a number of posts from a variety of media outlets and netizens at large began discussing a more inclusive version of puxin: One in which ordinariness and confidence could be celebrated, and to think outside the box of gender and scrutinize social norms unfriendly to the so-called “ordinary.” One representative comment hashtagged #为什么越普通要越自信# (#Why the more ordinary should be more confident#) argued, “Why can’t ordinary people be confident? Confidence is sinless and a good quality.” Generally, using “普信” as a commendatory term gained traction, encouraging people who had been marginalized by mainstream standards to embrace their uniqueness.

A simple Weibo comment seemed to champion the common person: “I’ve always felt good about myself, and I just realized that I’m a Puxin woman, so Puxin is now a positive word for me.” Suddenly, “ordinary, but confident” seemed to be the term of the hour, with a use in many situations: From bloggers using it to encourage people who might lack confidence – to how women approaching 30, who’d been set up on blind dates by their parents, might use it to cause “emotional damage” to their unsuspecting suitors.

The term’s popularity might have been due to how it touched upon deep cultural roots, in a collision of Chinese people’s perceptions and behaviors that have existed for ages, with those of newly emerging and growing values.

Confucian culture (the dominant Chinese culture until now) possesses collectivist undertones that an individual tends to “view oneself as interdependent and a member of a group rather than as an independent being” (Nickerson, 2023, p.1). A vivid example of this interdependent feature is a quote from the philosophy textbook of Chinese high-school education from Renjiao Press, a prominent textbook publishing company in China: “The realization of self-value needs to be in unity with society.” It emphasizes the greatest value of the individual comes when society’s needs are put first.

However, newer generations in China tend to prioritize self-growth and self-improvement over collectivist tendencies. This new use of “puxin,” demonstrates this by simply questioning these other long-dominant collectivist values.

The focus on social recognition was swirling in the vortex of public opinion when the new wave of “puxin” discussions broke out, as some netizens pushed back on the term in its underlying logic as a negative word, in which confidence relies solely on external recognition.

It has also become a trend to use “普信” as a compliment or encouragement for the “ordinary,” who fell short of social expectations but still identify with their own self-worth – a quite individualistic attitude focusing on internal recognition of value. This empowering usage of “普信” is challenging the dominant values in China where a sense of social worth is determined by achievement – and a type of achievement that always goes back to the good of the collective.

The trajectory of “普信,” “ordinary but confident,” initially unfolded as a cultural collision between patriarchy and feminism: It showed a breaking point of women’s anger over a long-held tolerance in Chinese society towards a certain type of male privilege in gender norms. Originating from Yang Li’s stand-up comedy and as a criticism of mansplaining and men assuming superiority, “普信” soon developed another meaning: It was okay to be ordinary but confident. This second meaning showed a revolt against high social expectations and social competition and resulted in a call for appreciating the good in oneself.

Nevertheless, the original, critical meaning of women calling out some men’s self-inflation may be far from over. Recently, after the premiere of the French movie “Anatomy of A Fall,” which explored non-traditional thoughts on gender roles in marriage, at Peking University on March 24th, two males (one as the host, another as a guest), were harshly criticized by female netizens for exhibiting superiority over and attempting to marginalize the female director and the female guest. The male host got booed three times by the audience for repeatedly speaking instead of letting the director talk about her movie. The male guest preemptively urged the audience not to take a gender perspective – but the director later stated that gender was a crucial topic of her movie.

The social debate over gender in contemporary China is nowhere near the end; instead, “puxin,” “ordinary but confident” may have just marked the starting point…

Authors’ Bio

Tong Yang (杨彤) is a first-year student from Chengdu, Sichuan, China. She loves music and yoga and is academically interested in history, philosophy, and gender issues. She wishes to explore sociology before making her major declaration.

Editor: John Noonan

Layout: Lexue Song