In an increasingly interconnected world, the necessity for effective communication has become ever more critical—nowhere more so than in the realms of healthcare. The Medical English Project (MEP), a visionary initiative, sprouted from a seed of necessity in 2019 to bridge the language gap between healthcare providers and international patients in the city of Kunshan. Launched by a talented student team, the four founders were Thanaporn (May) Thongthum, Reika Shimomura, Joy Xiao, and Caroline Robbins. Last year, new co-directors Ricardo Vargas, Nathaniel Woo, Liangyi (Rosie) Jin, and Helene Gu, obtained the CSCC Community Service Grant to further advance their initiatives. Under this brilliant tetrad’s guidance, the project progressed steadily.

The curriculum they developed includes essential medical terminology, patient communication skills, and specialized vocabulary tailored to various medical fields. Participating doctors not only are able to improve their English proficiency but also gain cross-cultural communication skills, thereby reducing the risk of misunderstandings due to cultural differences. Furthermore, the project offers DKU students a valuable opportunity to develop their own leadership and communication skills through teaching.

The Medical English Project promotes the internationalization of local healthcare institutions and provides positive momentum for inclusive community development in Kunshan. It stands out as a shining example of collaboration between DKU students and the local hospitals.

Helene Gu, in particular, has played a pivotal role in shaping the Medical English Project into what it is today. Her project management skills, leadership and vision have not only allowed the project to flourish but have also established a sustainable model for university-community engagement. This time, we invite Helene to talk in detail about the project and her experience leading it.

Helene, could you tell us about the inspiration behind the Medical English Project and what initially drove you to lead this initiative?

Hi, of course! Not everyone here knows, but the Medical English Project was actually one that was passed down to me and the other co-directors. It was established before the COVID-19 pandemic, around 2019 and was already running for 3-4 years by the time I even found out about it.

I found out about MEP around the end of my sophomore year (spring 2023), when I arrived at the DKU campus for the first time. When I met Renata in class, we quickly became friends due to our shared interest in going into medicine. One of our early conversations was about a shortage of volunteer opportunities for international students in China, but Renata was the president of the Young Leaders of Global Health Club. I got involved working with her club to host some events, but it was mostly one time activities and not entirely the type of volunteering I was looking for. Throughout the process though, I also got to know some of the initiatives of the club. I was really impressed when one of the members told me that she went to the hospital to teach doctors English every Friday, during their lunch time. Something about it made a profound impact on me. I realized this was exactly the opportunity Renata and I had been looking for. It was already established, and she didn’t even tell me. At the end of the year, when the club was recruiting, I knew I wanted to be part of this club. I was between applying for vice president and MEP co-director, and ultimately ended up choosing to pursue the Medical English Project. To me, the Medical English Project was finally a chance in China to do something real and long lasting, where being an international student wouldn’t be an inconvenience, but something of value.

How did you and the team first approach the local hospitals, and what were some of the initial responses from the local hospitals when they were approached with the idea of integrating Medical English into their practice?

Again, this is a common misconception. It wasn’t Ricardo, Nathaniel, Rosie, or me who approached the hospitals in 2019. However, the story of how MEP started has been told to us many times. At every MEP opening ceremony, Professor Joseph and Laura Davies of the Language and Cultural Center (LCC) and Dr.Yang of Kunshan No.3 hospital are very proud of the conception of this program.

Young Leaders of Global Health club leaders May, Reika, Joy, and Caroline had the idea and got connected with Kunshan No. 3 hospital. Dr. Yang was very receptive and even had similar motivations herself to help the international students and faculty at DKU. Her own English was very good, and Kunshan No. 3 has since had a very stable group of around 20 doctors who participate in MEP every session we have run it, including Dr.Yang herself. In fact, she and another doctor at Kunshan No. 3 (Marry) personally offer guidance with language and insurance to international students, and it’s really incredible. She has been a pivotal part in shaping this program.

With Kunshan No. 1 Hospital, the partnership did start under our co-directorship, but it was not us reaching out directly. Actually, it was Kunshan No. 1 that reached out to us through our club Vice President, Lingyi Shen. They heard about MEP at No. 3 and wanted the program at Kunshan No. 1 too, and we were more than happy to work with them. This happened in the middle of fall semester last year (2023). Dr. Huang wanted MEP at Kunshan No. 1, but she also came with clear ideas for how it would benefit her hospital, and we have spent a lot of time discussing and sharing ideas. Kunshan No. 1 is a much larger hospital, and their participation really renovated and elevated the program. In MEP’s history, it never felt like we were trying to convince the hospitals of anything. Overall, the hospitals are very proud of this program, and so are we.

In terms of logistics and planning, how were the DKU student volunteers prepared for their roles as language instructors? Or, can you walk us through the selection and training process of the volunteer DKU students who teach in the program?

I will preface my response by saying that DKU student volunteers of MEP are actually some of the most adaptable and passionate people I have worked with.

In my first year as co-director, there was really no training besides 1 hour long orientation. And the contents of this were about 30 minutes of language teaching advice from the LCC, giving out class and 1-on-1 doctor assignments, and the date of the opening ceremony. Besides that, the teachers just went for it. I really have to thank this batch of teachers and apologize to them, because obviously, this is not a well run program.

From this experience though, we have done more this year. The main change is more training. In addition to the orientation training, we had a session before the first week of classes to go over example teaching materials from previous years and online tools for course design, as well as how to reserve a room on DKU for classes, make a group chat, get doctors on campus using the access system, take attendance, All this is to say, there is a lot that goes into volunteering with MEP as a language instructor.

The application process usually runs for around a month. Applicants fill out basic information about what type of courses (beginner/intermediate/advanced) they would be interested in teaching. They also can choose to teach weekly 1-on-1 lessons or a class with a partner. The most important part of the application is 100 words about why they would be a good fit for MEP. We welcome students from any background, but the main basic requirements we check for are effort put into applying and demonstrated command of the English language. That being said though, we do get exceptional applications each cycle with students mentioning teaching experience, interest in connecting with the medical field, and powerful personal stories.

How does the MEP team ensure that the curriculum meets both the professional language needs in the medical field and the varied English proficiency levels of the doctors?

This is always the question. The short answer is that 1-on-1 classes are better for this. Doctors can learn the most by getting customized courses and a full hour of speaking practice each week. However, we do not have the capacity to offer private lessons to every doctor who wants it and so we want to make the group classes as valuable as possible. This year, using the CSCC grant, we decided to do research to answer this question from 2 sides.

First, what are the unmet needs of international students at DKU? This is actually what the professional language needs of the local hospitals stems from. In our survey and interviews, we found that a lot of what would make students more comfortable going to local hospitals is getting an explanation for why they are given a certain diagnostic test or prescription. Concretely, some international students aren’t used to the typical blood tests or CT scans used often. One interviewee also mentioned that an understanding of “laymen” or common words to describe conditions would be useful for doctors to know, even more than the technical medical terminology because this is how people tend to express their symptoms.

Second, what are the doctors’ experiences with MEP? These interviews were particularly insightful, because while we can interact with students quite regularly, it’s not every day we can sit down and really talk to the doctors about MEP. There are cases where one doctor in group classes is better at speaking and listening than the others and this makes others embarrassed to speak. Although we split between beginner and intermediate/advanced levels, there is still huge variance within classes. Some doctors have learned English for a month, others have learned it for over 30 years and are nearly fully fluent. As of right now, we hope doctors can learn from each other. Despite different levels, doctors shouldn’t be afraid. We actually also realized that it is moreso the confidence speaking than the actual medical terminology that matters to doctors, and this is a good thing, because it makes designing lessons easier, as we don’t need to focus as much on separating doctors by specialties. We were also told by a doctor that she makes presentations for work often, and would like to be the one presenting as part of MEP, which I think is a great idea for the final exams this semester. We were planning this out together at the interview, and it was really exciting, like, maybe we could have volunteers and other doctors vote for the best presentation to make it more engaging. I really wish we had thought of doing this research project earlier.

As you can tell, feedback is a big part of MEP. DKU student volunteers understand that the program is flexible to doctors’ needs. They design the course content each week and that really helps make the curriculum customized to each class. Again, the volunteer role is very active and not just executing a pre-prepared role.

Leadership often involves navigating unforeseen obstacles; could you share some challenges you’ve faced during this project and how did you overcome them?

One of my application essays is me complaining about MEP. I adore it, but it has sent me to a therapist, Chinese professor, and philosophy professor I never even took a class with because of the challenges this leadership has brought.

As previously mentioned, MEP began as 1-on-1 lessons at Kunshan No. 3 Hospital, with around 20 students and doctors. When I joined, we expanded to Kunshan No. 1, keeping the 1-1s at Kunshan No. 3 but adding group classes to both hospitals. Volunteers would go to the hospitals and teach every week. The problem began as teachers dropped out and demand grew. I felt frustrated as doctors wanted 1-on-1s but wouldn’t join classes. With requests for more volunteers at No.1 because they were bigger, and simultaneous requests to maintain the status quo because No. 3 was the initial partnership, it felt like I was in a tug-of-war.

I will say I’m really glad I took Chinese 301 at DKU, because it acquitted me with some understanding of Chinese culture. In particular, recognizing that the idea of “Guanxi” or “connections” is everywhere, but may be particularly strong in Chinese culture helped me understand and navigate this situation. I committed myself from the start to be impartial, and do everything in the open as much as possible.

When I got private messages from doctors about 1-on-1 courses and their passions to learn English. I apologized that it wouldn’t be possible this session, and the doctors accepted it well. However, at this point, I was also getting messages from students about whether they could teach multiple 1-on-1s or do 1-on-2s with multiple doctors, and I knew what was going on. This was not how the program should have been running. This experience was a turning point in how I thought of MEP, because at the end of the day, student volunteers were providing hospitals with a free service in high demand. While I was preoccupied with meeting the needs of the two hospitals, nobody was advocating for the students. Many were just freshmen under this pressure to deliver. There were obviously no bad intentions from anyone participating in a program like MEP, but boundaries had to be established.

When I finally talked to the co-directors, I found that though I had tried to hide the problem, even our supervisors knew. When we sent a message, both hospitals agreed. We made one group chat for both hospital leaders and the codirectors. We put volunteers first and acknowledged the contributions and requests of both hospitals. Collaborative renovation began from these axioms.

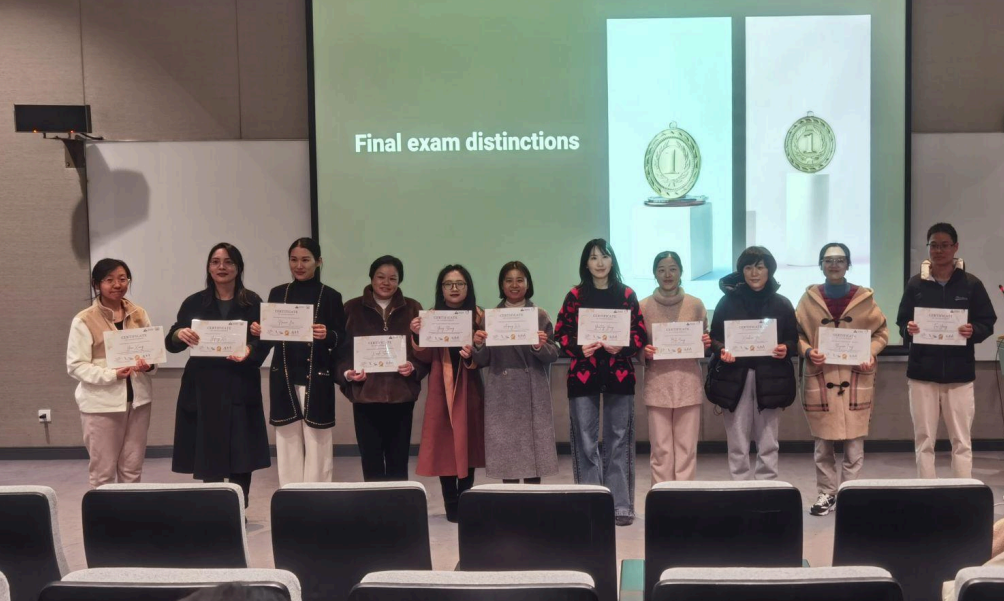

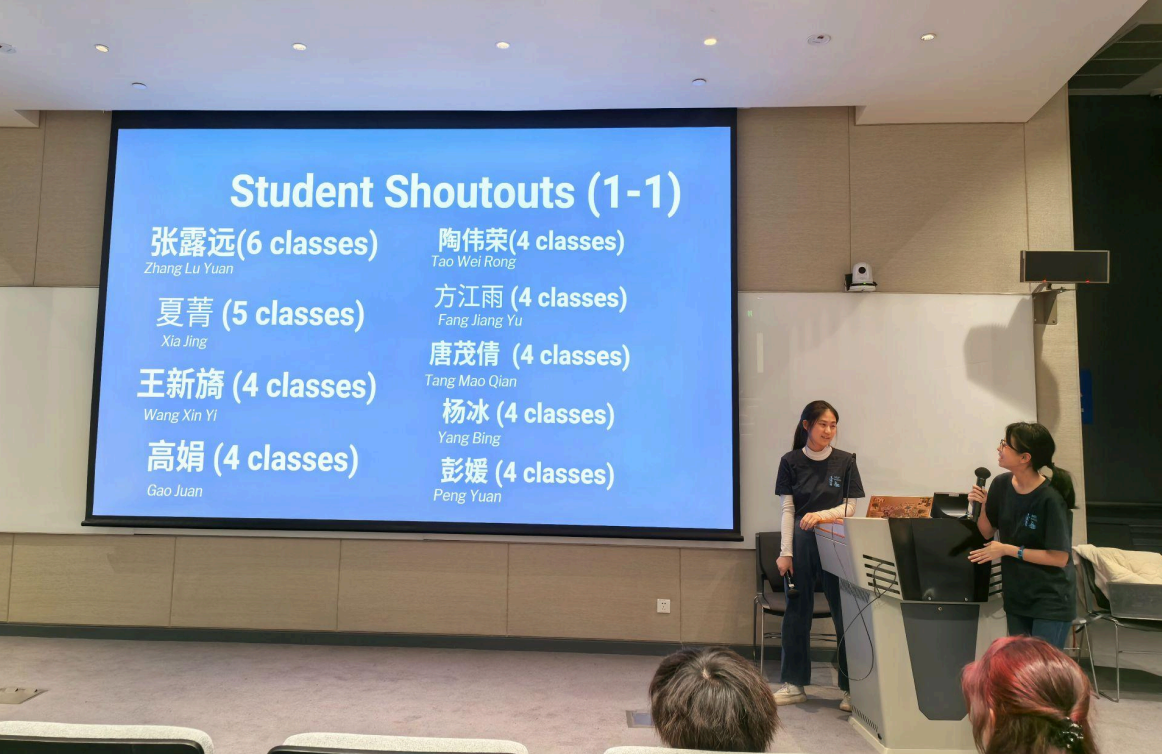

This is what I said last year, and this year you can see the changes. There is an application for 1-on-1s based on writing a paragraph (in Chinese), and doctors are chosen based on merit/effort. All group classes have been moved to DKU, both to encourage interactions between doctors of both hospitals and to make teaching easier for student volunteers. Through MEP, I also let go of an unconscious cynicism of “if you need a job done well, do it yourself”. My potential on this capable team is far beyond my own. Ricardo’s promotion of the program has led to record student interest in MEP. Chuwei Fan has made a system to track all the doctors/students and their attendance this year, so we are rewarding doctors and students to motivate participation. Holly McClure has designed many new logos, and with Rosie’s help we ordered T-shirts to build MEP connections and visibility in the community. We bought meal coupons for the opening ceremony so doctors and volunteers could get to know each other over lunch, and again, we have more training to support volunteers. We are still in the process of improving, and I don’t think there will ever be a lack of things to improve with MEP, but the two main takeaways for me are to ensure the project benefits everyone (students, doctors) giving their time and effort to be involved and to trust others more, for the sake of the project and my own.

The Medical English Project emphasizes not just language learning but also cultural exchange. Could you share some insights on how this has been received by both the medical professionals and the DKU community?

Yes! Personally, one of the funniest moments in an MEP class Renata and I taught was when a doctor asked another doctor “What’s wrong with you?” in a roleplay practice, because despite being grammatically correct, it’s not how a doctor typically asks about a patient’s condition in English. “How are you feeling today?”, or “what brings you here?” are probably more like what patients are expecting to hear. Students from the DKU Written and Oral Communications class (WOC208) taught by Professor Davies also collaborated with MEP to teach 2 lessons on intercultural communication (taught by Shiran Yuan) and body language in communication (taught by Yuri Park) that were highly well received by the doctors. Finally, I hear from a lot of volunteers about all sorts of things doctors talk about in 1-on-1s. A friend’s sessions often went overtime by 1 hour each week because she was teaching additional lessons about the United States geography and laws. I know which doctors are interested in traveling, baseball, Western food, and more based on teachers asking me whether it’s okay for them to be talking about non-medical topics too. Over time, the answer has shifted from “don’t let me know about it” to a solid “yes”. Cultural exchange in addition to Medical English learning is really important to build connections between the doctors and students.

How do you measure the success of the program, and could you share a particularly rewarding outcome or success story that has resulted from this initiative?

As I previously hinted at, my main metric of success is how many people benefit from this program. In particular, I’m looking at the benefits to the DKU student volunteers. Even more pressing than the long-term benefit MEP will bring to international patients or the English capacities of the hospitals is the enthusiasm of volunteers coming into our project.

I have measured failure. The first time we expanded to Kunshan No. 1, I know the project was a lot of strain on volunteers without much sense of reward. I looked at the retention rate of most students not continuing MEP after one semester. I know that regardless of what I do, the Medical English Project is not for everyone, and I’m glad that there were so many people who decided to give it a try and stuck through with it for the semester. However, I also know that there are ways that it is possible to do better from the co-director end.

My success is the volunteers who continue with MEP, and excel at it. I will call out Jieni Chen, Bonnie Cabot, Xavier Monroy, Quinn Bradley, and Holly McClure, but there are more people. I know that it’s obviously not because of me or the rest of the co-directorship that people stay in MEP. It is almost certainly the connection formed with the doctors that makes the program rewarding, but it is particularly meaningful to me when volunteers and their doctors choose to stay in the program. I also appreciate the doctors who continue to take courses, because, while it is not also not because of me, I am glad that there is value for them in the program taught by the student volunteers. These are DKU students and doctors who want to do good in the world. This is clear when they apply for the program in the first place, and as a co-director, I’m trying to facilitate this process.

What does the roadmap for the Medical English Project look like going forward? Are there any particular areas you and the team are aiming to develop or expand; Or, are there any potential partners you hope to include?

I would be lying if I said I didn’t have ideas, but I do not have much time left at DKU. There is so much further MEP can go in terms of research, curriculum improvement, participant satisfaction, and so on.There are many hospitals in the Suzhou/Shanghai area. When members go to other hospitals and mention they teach for MEP, these hospitals often want to join. A medical student from the National University of Singapore (NUS) reached out to us about an exchange program that was too logistically challenging to arrange this year, but I hope it becomes possible in the future. Not to mention, besides my focus on getting the fundamentals of the project down, there is room for collaboration with the MediHealth Podcast and Medic Mindset clubs. Our media team (Lu Yang and Jingyi Wang) set up a photo wall for the first time at the recent Midterm Ceremony. MEP graduation regalia and hoodies were great ideas that I unfortunately did not prioritize this time. There are many opportunities for refinement and expansion, but I’ll leave it to our incredible future co-directors to make MEP more impactful and cooler.

As a student leader and participant in the project, what have you learned from this experience, and how has it impacted your career or personal development?

I have grown so much from MEP. I think it is the first true leadership experience I have had, and it doesn’t look like what I thought it was.

I mentioned that in times of difficulty, I turned to philosophy. There are three that have since shaped me profoundly. A leader embodies a clear and steadfast vision, making a way for others with a shared interest to take part in the goal. A leader must keep people as the priority, and never use anyone as means to an end. In this, a leader is a guardian, a guide, or a public servant.

Today, I still lack many of the traits people traditionally think of in leaders, but I know I am succeeding in the ways that matter to me. If a well-led project is one that allows all team members to make it their own, I would call MEP a success.